Meet Stephen Malinowski ’80 (CCS Music Composition)

CCS Alumnus reflects on his journey as a trailblazer in music animation

When Stephen Malinowski’ 80 (CCS Music Composition) graduated from the College of Creative Studies (CCS), he never imagined that the explorative, radically curious nature of the College would be so central to his life’s work. Yet two decades later, Stephen has built his career on the creation of knowledge through hands-on experimentation. His most notable creation, the Music Animation Machine, revolutionizes music cognition by focusing on the visual—the way the musical notes in a score dance in a musician’s mind. By creating a visual representation of his understanding of music, Stephen has transformed the way he and others are able to engage with even the most complex compositions. However, his pathway to success was not straightforward. The musical mastermind pivoted many times, guided mostly by his willingness to take on many endeavors and his urge to create. True to the spirit of experiential learning at CCS, his Alma Mater, Stephen continues to learn best from doing. As he explains, “I'm not much of a student in the normal sense; I can't sit down with a book and learn something by just reading it… Most of what I know is the result of my own direct experience.”

“I'm mostly motivated by curiosity: I listen to a piece of music and wonder what would that look like.”

––Stephen Malinowski ‘80 (CCS Music Composition)

The Early Years

In his youth, Stephen enjoyed music, science, and mathematics. However, a calculus class at his local community college revealed a formerly unbeknownst learning challenge that prompted Stephen to evaluate his life’s ambitions. During this time, an encounter with John Carbon ‘76 (CCS Music Composition) allowed Stephen to learn about CCS, setting the stage for his musical journey.

Despite being a music composition student, Stephen did not shy away from other fields of study. The Music Animation Machine inventor spent his time at CCS exploring his interests and developing new skills, ranging from music to computer science to letter writing. In fact, his time spent practicing with a CCS computer terminal later gave him the confidence to move forward with developing the program for the Music Animation Machine. Stephen learned primarily by doing. As he explains, “I'm not much of a student in the normal sense; I can't sit down with a book and learn something by just reading it… Most of what I know is the result of my own direct experience.”

While his time at CCS provided him with an abundance of musical knowledge, Stephen credits the lessons learned outside of his music classes as most significant. Two experiences in particular share a common theme in him finding the silver lining.

The first time it happened was when Stephen was deciding to write a letter about his difficulties in narrative prose to his then-professor, CCS Founding Provost and Professor of English Marvin Mudrick. In response, Mudrick highlighted Stephen’s strengths, reading the letter to Stephen’s classmates and praising his talents in letter writing.

“Mudrick was the first person I encountered who was a master of his craft so, coming from him, his comment meant a lot, and although I gave up trying to be a composer–once my cognitive limitations became more obvious to me–I've put a lot of effort into letter writing since then.”

––Stephen Malinowski ‘80 (CCS Music Composition)

The second experience took place prior to Stephen’s graduation when he was asked to be a music guest lecturer at the College. Though the experience confirmed for Stephen that perhaps he was not meant to be a music professor, it provided an impetus for Stephen to consider alternative careers.

During that time at the College, Stephen also was developing a deep interest in the internal aspect of score reading, that is, what goes on inside the mind of a music reader. He would spend hours listening to music while following along with the score, often attending concerts with a copy of the score in hand.

As Stephen explains, “Music cognition is possible because we're able to perceive musical sounds through analogies between them and other things, like language, physical motion, emotion, and vision.” While this is automatic, learning what to pay attention to allows us to engage with, or appreciate music at a higher level.

Stephen was gaining insight into a third, less-common sense of music cognition: sight. In addition to hearing and feeling, musicians with synesthesia or a strong visual imagination can sometimes see the notations of a piece within their minds. For Stephen, the notes within a violin piece were walking, dancing, floating, flowing, rolling—in ways that were analogous to their musical motion.

However, when attempting to visualize more complex compositions, this musician hit a wall. Forming analogies is mentally taxing and requires a lot of brain power. In response, Stephen began exploring ways to reduce the overall cognitive load, leaving more energy for forming analogies. As he quickly realized, a visual representation did just that. Stephen notes, “A visual representation helps in two ways. By visualizing the analogies, it can make them easier to recognize. And, by giving you something to do with your eyes, it can help you keep your attention focused on what's going on in the music.”

Following CCS Commencement, this alumnus explored a diverse range of experiences including as a pianist, a music teacher, a manuscript copyist, and a software engineer. Though Stephen did not have the foresight at the time, he now acknowledges the skills and insight these experiences provided.

“Looking back on my life, I recognize many things I happened to learn that shaped my approach to what I'm currently doing, including: piano lessons as a child, teaching myself guitar, recorder and other instruments, working as a professional music manuscript copyist, learning to compose, directing musical ensembles, studying geometry, trigonometry, physics ...I didn't do any of these things with the idea that I would ever use what I learned for something in the distant future. I didn't conceive of an animated graphical score until one was produced by my imagination…and it's only recently been obvious that this is my life's work.”

––Stephen Malinowski ‘80 (CCS Music Composition)

The Birth of the Music Animation Machine

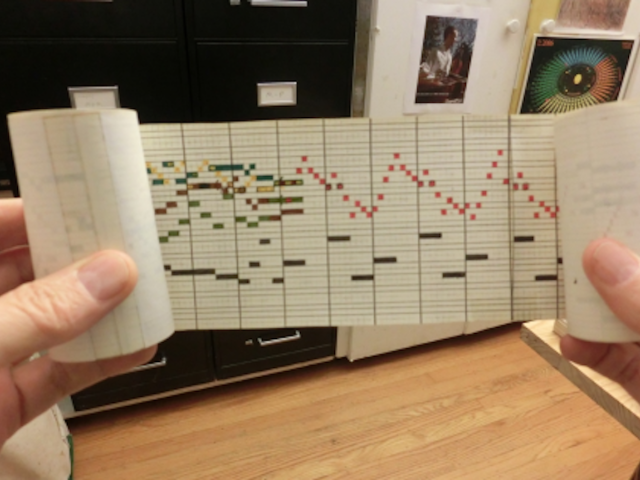

In its earliest years, the Music Animation Machine was a hand-drawn scroll. Then, in 1982, Stephen made the transition to computers. Due in large part to his exposure to computers at CCS and UCSB, the alumnus felt confident that he could accomplish his music visualization software through experimentation.

He purchased and learned to program his first computer, leading to a job in software engineering in 1984. The years that followed were spent working on his project with notable progress in 1985 via his Atari 800 and 1988 on his IBM personal computer. Stephen ventured away from piano-roll style scores, experimenting with ways to visualize musical elements such as tonality, rhythm, consonance and dissonance, tuning systems, interval relationships, timbre, and canonic structures.

While working at a Silicon Valley startup in 2001, Stephen had an eureka moment. The startup developed its audio analysis software inspired by the neurology of the human auditory system. This led Stephen to change his approach to graphical scores, particularly in his piano-roll displays: “Previously, I'd been thinking of my displays as showing what was going on in the music, but I began to think of them as showing what was going on in the mind of the listener—specifically, what was going on in my mind.”

As a part of this new outlook, Stephen began to emphasize what he felt in the music, reading between the lines of melodic scores. What initially started as primarily balls and bars grew to a collection of over 200 methods of rendering notes visually. For Stephen: “I've come to see what I'm doing as a form of orchestration in which the notes are assigned to visual instruments instead of aural ones. My process is very much like orchestration, too: a large part of the design is specified in a conventional score.”

The Present

Since retiring from the software engineering industry in 2010, Stephen has focused on his music animation. He embraces his role as a trailblazer in music animation and spends his days digging deeper into his graphical scores with the goal of uncovering hidden analogies. He said: “Because I'm exploring new things, there's some value in all my experiments—as examples of both what to do and what not to do. And, I know that what I'm doing is still ‘early work’...and I'm still at the point where everything I do seems far less than perfect. So, I don't worry about getting things perfect; nothing I'm doing is perfect. I'm still just scratching the surface.”

Advice to Current and Future CCS Students

“Learn lots of different kinds of things that interest you.”

––Stephen Malinowski ‘80 (CCS Music Composition)

Stephen encourages all students to pursue their passions and never stop learning. From his own experience he advises students: “Through no application of will, no foresight, and with no intentional design, I've ended up being able to do something interesting, rewarding, challenging, and which lots of people are finding value in. How did that happen? The only constant I can see is that I did things because I was interested in them for their own sake. I suspect that this is why I was good at them: I enjoyed learning about them.”

Learn more about Stephen’s inspiring journey here.