Lifelong Learning

CCS Art Faculty member, alumnus, and renowned artist shares his CCS experience and how childhood shaped his art

Hank Pitcher (CCS Art ’71) was one of the original 50 students when the College of Creative Studies (CCS) opened its doors in Fall 1967. He joined the CCS Art faculty upon his graduation in 1971 and has remained with the College ever since. Now a renowned landscape painter, he teaches Art in CCS. Pitcher, a native of Isla Vista, graciously invited us to his studio on UCSB’s West Campus to talk about how the College has evolved over the past 50 years and how his early experiences impacted his work.

CCS: How did you first hear about CCS?

Hank Pitcher: Well, when I was a senior in high school, my mother showed me a small article in the Santa Barbara News Press announcing a newly formed College of Creative Studies at UCSB and that seemed interesting to me. In high school, representatives from different colleges and universities were coming in to talk to students, and I used to go to those meetings. A week or so after I saw the announcement, [Marvin] Mudrick [the founder of CCS] came and spoke to a small group of students, and he was very interesting. It was something that I hadn’t experienced before. The way he talked, his energy, and his intellectualism were so impressive.

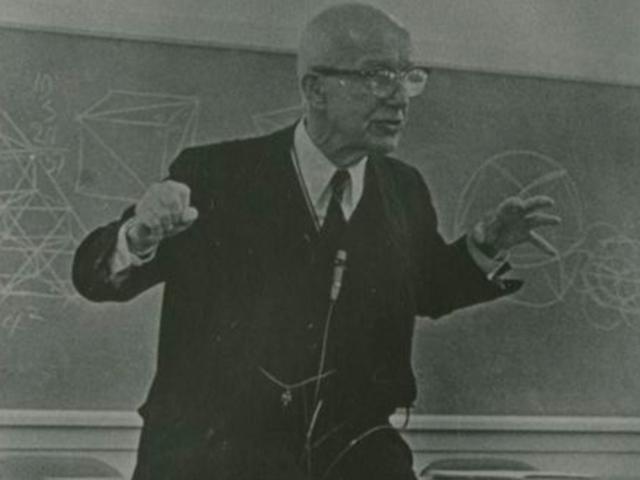

At that point I was a senior at San Marcos High School and looking at different colleges to go to mostly focused around football because I was offered a lot of good football scholarships. I was looking at big powerhouse schools across the nation. UCSB had a football team at the time and they had wanted me to play there, but it wasn’t a big time program and I figured if I was going to play I wanted to play with the best. Ed Loomis, who was the chair of the English Department at the time, set up a meeting with me and said that he had heard from Mudrick that I was interested in the CCS program so he wanted to talk to me. Both Loomis and Mudrick were much more interesting than the football recruiters. It was a different kind of dialogue than I had with any other adults. The more I found out about CCS, the more interesting it got to be. The people who were recruiting me to play football were talking about how there were weight rooms in the dorms and easy classes. The emphasis was on how easy the classes were going to be and I was not interested in easy classes. I was interested in learning about art and literature. The College wasn’t about being easy—it was about being rigorous. I decided to go to the College of Creative Studies and I figured I could still play football because they had a team here. School started and the football coaches kept advising not to take hard classes, but I went to a lecture by Buckminster Fuller that the College had hosted the first week of school and that was a whole other level and just so interesting and I thought to myself, ‘this is what I want to be doing. I want to be hanging out in the College with people like this and painting, not hanging out with people on the football team.’ So I quit the football team that day and just focused on CCS.

CCS: From what we have seen, the Buckminster Fuller lectures were very important in the early years of the College. Can you tell us more about these lectures?

HP: The first year, he came for about two weeks and every evening he would go into this room and he would look around at the audience and then he would close his eyes and just start talking. Occasionally he would open his eyes, which were magnified by his thick glasses, and he would look intently at people in the audience to see if they were following him. Then he would close his eyes and take off again. He would go on wild tangents but always end up tying everything together into a remarkable new way of seeing the world. I am still thinking about things he said back then.

CCS: Over the years, what has surprised you about what has changed and hasn’t changed?

HP: Over the last 50 years, there has been pressure to make CCS more conventional, more like everything else. I am surprised that CCS has been able to resist things like changing the name and having grades—making it more conventional. A non-punitive grading system was a radical idea in 1967 and still is. One change that I miss is the tradition of unusual / humorous course titles and descriptions. “Walking Biology” has survived. But John McCracken, now considered one of America’s most important sculptors, was criticized for teaching “Astral Traveling.” That course description was very good.

CCS: With turnover in the faculty and students, why do you think the College has stayed so true to Mudrick’s ideals?

HP: It is a funny thing. The College just attracts certain people. Around Coal Oil Point where my studio is, they did some restoration and took out some exotic/invasive plants. All of a sudden all of these animals started showing up that nobody had seen for years and years. Where did they come from? How did they know? The College is like that. The thing about Mudrick is he had the highest respect for students. He was really interested in students and he believed that they could do great and valuable things. Don’t tell them what they should do; find what they want to do. Ask them questions, let them ask you questions and free them up. I think the faculty at the College have the same feeling. They aren’t coming in as authorities, they don’t have all the answers, they are coming to learn and to develop colleagues. You invest a lot of time in a student because you want them to get to the point where they can ask you hard questions and you can start to learn from them. The best Creative Studies teachers are teaching new and different classes all the time and are evolving, even when it is the same subject.

CCS: Did you become a faculty member right after you graduated in 1971?

HP: When I was a senior, getting ready to graduate, I started traveling around and looking at graduate programs and visiting other Colleges and I wasn’t finding anything that was really exciting to me. For the last 50 years, including when I was a student, there has been a theme in academia that painting is dead. I was not interested in that idea. It is still being talked about, but painting continues to be, in some ways, the most popular and the most economically important field of visual art. I was lucky as an undergraduate to work with Paul Wonner, who was a significant painter, and I learned a lot from him. The other programs I was looking at were not so interested in painting. I was thinking about this one afternoon and Mudrick came to me and he asked me if I was interested in staying on for the year as a lecturer. I was having some recognition and success professionally, and I thought, ‘Well that might be a good idea,’ because I could continue to do the work I wanted to do and I could keep looking for a place to go for graduate work, find a better place. But one thing led to another and I just haven’t found a better place to be, so I am still here.

CCS: A lot of people would be burnt out after teaching for over 45 years. What keeps you coming back?

HP: I have only taught half time over these many years. My primary focus is on my own work—painting this landscape, this lifestyle, and this part of the world. I think if I had a traditional full time teaching position and I had to give grades and I had to deal with students who wanted a grade to stay on a sports team, I wouldn’t do that. I am just so uninterested in that kind of teaching. In every class that I teach here, by and large everyone who is in that classroom is there because they want to be. The students ask interesting questions and I can ask them questions. It is stimulating—intellectually and artistically. Additionally, the faculty that are on campus, many could teach anywhere in the world, have decided to teach here. They choose to be here because of the place—it is a privilege to get to know them. Over the years, I have taught classes with people from other disciplines. From Bruce Tiffney I have learned about geology, botany, and other aspects of science that are thrilling and important to me. I don’t know of and can’t imagine a place where it could be as good as that.

I am of that age now where a lot of my contemporaries are retiring. I think you retire when you are doing something that is not interesting or that you don’t want to do or maybe can’t do anymore. If you are interested in what you are doing, you want to keep doing it. It is more than ‘life long learning’ it is just being alive. Being alive is being curious.

CCS: Take us through the class that you taught with Bruce Tiffney.

HP: We did that class for almost 20 years. It evolved into three weekend meetings during the summer. The first weekend we would meet on West Campus for an introductory lecture and then paint all day with two critiques. It was a run through for the following two weekends when we would go up to the Sedgewick reserve and stay there from Friday through Sunday. We woke everyone up before dawn to paint the sunrise.

Bruce gave a lecture every afternoon about the botany and geology we painted. Things like the different types of oak trees and the subduction zone that ran through the reserve. After a break in the middle of the day, we would paint until sunset. Then we had amazing meals. A benefactor donated money to allow us to cater all organic local food from a French trained chef. Then we often sat outside and looked at the stars and talked. That was the basic structure of the class.

CCS: How do you approach teaching a typical CCS class?

HP: Most students are used to classes where they are told what they should do to get a grade. I discuss what they could do to expand their own work and increase their understanding of the history and tradition of drawing and painting.

CCS: What was an example of one of these classes?

CCS: Well I taught a class with Charles Garabedian titled ‘Man, Tragic and Heroic: Narrative Paintings and War Movies.’ We watched old war movies and looked at narrative painting and looked for connections between them. It was a fabulous class and I learned a lot about war movies and World War II because he was a gunner on warplanes flying over Germany.

CCS: What do your paintings focus on?

HP: My paintings are about the natural and social history of this part of California - mostly the beach. I see surfing and the beach as mythic subjects and I see the Greek myths acted out constantly on and just off shore. Also I am interested in the incredible biodiversity and the geology here. In the stretch of beach between Campus Point and slough on West Campus there is more invertebrate biodiversity than anywhere else known on the planet.

CCS: You were raised in Santa Barbara…

HP: Yes, I grew up about 400 yards from where we are sitting—in Isla Vista.

CCS: How did growing up here influence your work?

HP: When I was young, UCSB was still primarily focused on teaching and at that time there was a very strong relationship with the IV elementary school (where I was in the first graduating class). The facilities of the University were open to us. I loved the library and the pool and the range of public events. That was a very positive thing, but seeing how the growth of the University affected the landscape—there were only 100 families living here when I was growing up—was a negative. We lived in the middle of Abrego road and from Abrego road to the freeway it was just fields of wildflowers. Seeing the growth and to see the really shoddy apartment buildings that were built and to see the destruction of this paradise has been very difficult.

CCS: How did the fact that you have seen that destruction first hand affect what you paint?

HP: Well it has affected me in complex ways. When we were kids, the developers came in and destroyed what for us was sacred ground—these fields of wildflowers, eucalyptus forests, and vernal pools full of frogs. And the crowds of new residents stripped the beaches clean of crabs and abalone and mussels. As kids we would try to save our beloved landscape. We snuck out at night and moved surveying stakes around, hid tools and buried supplies. Once we got a tractor started and drove it over the cliff. We were very young and naïve. Later I came to realize that painting, celebrating the landscape by painting it, not in a sentimental way, but in a truthful way, helps preserve it. If you have never seen it, you don’t care if somebody destroys it. That has become part of my teaching; I try to inoculate the landscape into the students. When you learn a little bit about nature, when you get exposed to it, you realize it is really interesting. It is much more interesting than, well, Game of Thrones—being out in nature is much more interesting than TV. I think in some ways I realized that obstructing the construction was not going to do me any good or the landscape any good, but painting it and being excited about painting it and sharing that enthusiasm with people outdoors sort of changes the discussion.

CCS: How do you think paintings compare with photography?

HP: I think they are different. A photograph is usually a fraction of a second and it documents where everything was at that exact moment. Paintings take a long time, and are about experience over a period of time and moving things around in the picture to talk about experience. This is a generalization – there are definitely photographs with long exposures and that have been manipulated in many ways, but I think that photography is more about documentation and painting is more about contemplation.

CCS: Anything else you would like to say about CCS?

HP: Early on I was surprised that there wasn’t a line down the street of students wanting to enroll here. After a while I realized that not many undergraduate students are sure about what they want to do in their life. A few do, and they quickly understand that CCS is a place for them and they want to enroll here. There are not that many. I relate to those students because I was one of them.

This article appeared in the CCS 50th Anniversary Newsletter.